Malick and Me: BADLANDS and DAYS OF HEAVEN

On this lovely Southern Californian afternoon, I fondly recall a wintry and, nonetheless, lovely New England night: a Friday of my junior year in high school, wherein I watched a 139 minute film written and directed by a man whose picture on IMDb exuded a mystical and avuncular spirit, reigning from the old fields of Ottawa, Illinois, and Bartlesville, Oklahoma, a Harvard College graduate (Philosophy, summa cum laude), Phi Beta Kappa inductee, Rhodes Scholar, an American Film Institute Conservatory alumnus…a man named Terrence Malick. And on that wintry and lovely Friday night, my stomach brimming with cream soda, pepperoni pizza, Twizzlers Pull ’n’ Peels—the naive works—my mind, utterly entranced, my heart, hitherto enamored only by the childhood favorites (Viz: THE NIGHTMARE BEFORE CHRISTMAS (1993), JAMES AND THE GIANT PEACH (1996), THE LORD OF THE RINGS TRILOGY (2001, 2002, 2003), THE LAST SAMURAI (2003)), now novelly enamored by an exquisite rendering of the American pastoral, all its glory and foibles and hidden philosophies: THE TREE OF LIFE.

I hope that night will ring true and well for the rest of my days, and currently as a freshman in college, it maintains unwavering, so much so that a written series, tracing Malick’s vector from BADLANDS to VOYAGE OF TIME, the influences of his upbringing in the Midwest, his philosophical predilections—Kierkegaard, Heidegger, Wittgenstein—and scholarly past, his reverence for nature, his rectitude, becomes ineluctable for his latest film, SONG FOR SONG, which debuts at the Austin, Texas SXSW Film Festival in approximately 1,000 hours. Oh, boy. The girl opposite me at the table in the library, three seats down, to my right, gives me a sour, distasteful, why-are-you-so-happy-go-lucky? look; she must be studying for her MCATs, GREs—her cathexis screams mortal agony; perhaps an injection of Malickean cinema would bring her to the light…?

Hey, honey. Uncle Terry wants you to put down those GRE flashcards

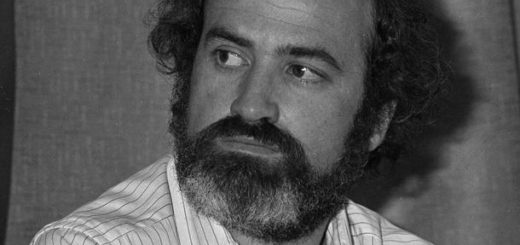

After graduation from Harvard College and his mentorship with renowned academic Stanley Cavell, a young Malick skipped across the pond to, presumably, pursue a doctorate degree in philosophy at the prestigious Magdalen College, Oxford, as a Rhodes Scholar. He fluently spoke German, having to do so because of his academic specialization—the Danish, German, and Austrian big guns: Kierkegaard, Heidegger, Wittgenstein. Malick left Oxford, supposedly due to a disagreement with his thesis advisor, Gilbert Ryle, regarding Kierkegaard’s, Heidegger’s, and Wittgenstein’s theses on the concept of world. Northwestern University Press published a remnant of Malick’s academic stint, however, in 1969; his translation of Heidegger’s THE ESSENCE OF REASONS remains today to be an assured scholarly work. Malick returned to the United States to find employment as a professor at M.I.T. and as a freelance journalist, but, thankfully, his incipience as an artist came to fruition: Malick enrolled at the American Film Institute Conservatory, in Los Angeles, in 1969—the inaugural class.

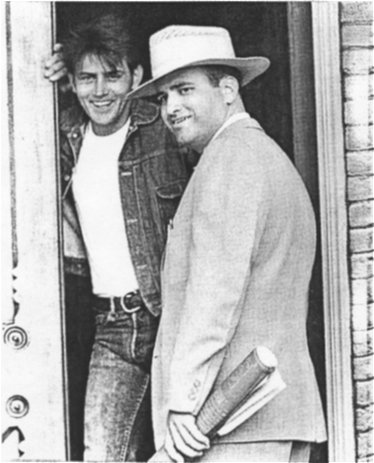

Malick began developing a film at age 27 during his second year at AFI, drafting the screenplay, loosely based upon the true story of couple Charles Starkweather and Carol Ann Fugate’s murder spree in the year 1958, while road-tripping through the West—the draft would end up becoming the 1973 picture BADLANDS. Executive producer Edward Pressman secured half the film’s funding, Malick, $25,000 from personal funds, and the remaining money provided by professional dentists, doctors, and lawyers totaling to a fractional $300,000. BADLANDS stars a strapping buck in Martin Sheen, playing the role of Kit, a garbage collector of the James Dean ilk, and a nubile fair maiden in Sissie Spacek, playing the role of Holly, a 15-year-old Romantic swooned by the foregoing devil-may-care incarnate. Both are thrust into a violent, chaotic, and, conversely, idyllic and saccharine love affair, the desperate, forlorn dash from, principally, the law, spanning the Midwest, the badlands of Montana, and north to Saskatchewan after Kit murders Holly’s patriarchal father.

James Dean and Uncle Terry

Rather than honing in on plot and story machinations, characterization, or aesthetic technicalities, I submit that the beauty of Malick’s debut feature lies in its Midwestern landscape, the sleepy and rustic “Earylism,” (term coined by the great Richard Brody) that permeates the film from beginning to end. Certainly a banal setting, though notwithstanding, a setting amply capable in mesmerizing the willing audience. Despite our director’s prodigious past in academia, his Harvard A.B. with distinction, Rhodes Scholar endeavors at Magdalen College, Oxford, a brief philosophy professorship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, journalistic contributions to NEWSWEEK, THE NEW YORKER, and TIME, he, remarkably, never leaves behind his tried-and-true Midwestern roots. Malick grew up in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, attended St. John’s Episcopal School in Austin, Texas—he played football for heaven’s sake!—and, never, never, does Malick disdainfully paint the Midwest, the ol’ sentimental heart of Americana, as tripe, fly-over territory, the antithetical land to the culture and sophistication laden in the cities on different ponds: New York or Boston, Los Angeles or San Francisco. Critics have labeled Malick with the following words: terribly pretentious, highfalutin’, ponderous, self-indulgent, nemophilist. But, be it BADLANDS or TO THE WONDER, Malick casts a grateful and perspicacious eye out toward the horizon of his homestead.

DAYS OF HEAVEN, Malick’s second feature film, produced on a fractional studio budget of $3,000,000, thanks to Paramount Pictures CEO Barry Diller and fellow producer Bert Schneider, garnered ubiquitous critical acclaim, an Academy Award for Cinematography (recipient, Néstor Almendros, a complicated honor considering Haskell Wexler shot a large majority of the final edit), and for Malick, the Best Director Award at the Cannes Film Festival. Richard Gere, another strapping buck, stars as Bill, a headstrong Chicago layman. Brooke Adams stars as Abby, his loyal, salt-of-the-earth girlfriend, who poses as his sister so that romantic gossip may be avoided, and the youthful and pertly Linda Manz stars as Abby’s sister, Linda. Sam Shepard plays the farmer, an affluent, albeit severely forlorn and terminally ill, wheat-field proprietor. Bill, after murdering his steel mill boss in Chicago, flees with Abby and Linda to the Texas Panhandle in search of pay. The farmer and Abby spark tumultuous romance, and a shrewd, nefarious Bill convinces the novel cozener Abby to marry, so that she may inherit her spouse’s estate upon his eventual passing—a violent, fraudulent, and conversely, idyllic and saccharine love triangle ensues; sound familiar?

Folks, take a two-hour breather. I’m gonna film this flock of birds

Malick’s lurid return to the Midwestern landscape, by way of the Texas Panhandle, comes as no surprise. And his profound, compassionate, and pious reverence for said land, its natural composition, its history—molded by characters such as Bill, the farmer, Abby et al.—perpetuates a prospect grounded in the at-home experience, a prospect devoid of pretension, unprecedentedly beholden to its subject. Abby’s voice-over provides a contrapuntal narration (concept courtesy of Matt Zoller Seitz), a narration synchronously underpinning the diegetic and nondiegetic elements of the film, albeit a narration detached from the narrative—Abby’s character, at times, narrates in the past tense, in a wistful recollection. Malick’s decision (one could find a manifold of reasons as to why he would do this) to frame the narrative within the young girl’s perspective emulates his vision—naive, melodramatic, overtly sentimental—of his homeland. I want to reference the film’s opening sequence, in particular. I find this scene to be the apogee of Malick’s Midwestern paintbrush and palette. Malick captures the Panhandle setting rapturously, as Bill, Abby, and Linda travel via rail, along with the indigent multitudes, seeking prosperity and security in the plains and their amber waves of grain. There are several inserts and medium close-ups of weathered travelers and their children that contrast beautifully with the far-reaching expanse of their environment; the contrast functions not to crudely depict an isolated, pitiable existence, but to meld character and setting into one being, one bygone epoch, forgotten by those who disdainfully dismiss.

In his essay “E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction,” from the collection A SUPPOSEDLY FUN THING I’LL NEVER DO AGAIN, David Foster Wallace writes on his topical state of literary artistry, circa 1997 (the following thoughts could be applied to any art form in the 21st century):

The next real literary “rebels” in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels, born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles. Who treat of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction. Who eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue. These anti-rebels would be outdated, of course, before they even started. Dead on the page. Too sincere. Clearly repressed. Backward, quaint, naive, anachronistic. Maybe that’ll be the point. Maybe that’s why they’ll be the next real rebels. Real rebels, as far as I can see, risk disapproval. The old postmodern insurgents risked the gasp and squeal: shock, disgust, outrage, censorship, accusations of socialism, anarchism, nihilism. Today’s risks are different. The new rebels might be artists willing to risk the yawn, the rolled eyes, the cool smile, the nudged ribs, the parody of gifted ironists, the “Oh how banal.” To risk accusations of sentimentality, melodrama. Of overcredulity. Of softness. Of willingness to be suckered by a world of lurkers and starers who fear gaze and ridicule above imprisonment without law. Who knows.

Malick’s artistry epitomizes Wallace’s prescient sentiments (this becomes especially true after the 20-year hiatus between DAYS OF HEAVEN and THE THIN RED LINE). I am most impressed, not by Malick’s Harvard letter, matriculation at Oxford, his M.I.T. stint, AFI pedigree, nor his scholarship in philosophy, understanding of Kierkegaard and Wittgenstein, his Heidegger translations; no, I am impressed by his unfettered appreciation for home; his courage to “endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles,” “to risk the yawn, the rolled eyes…accusations of sentimentality [and] melodrama.”